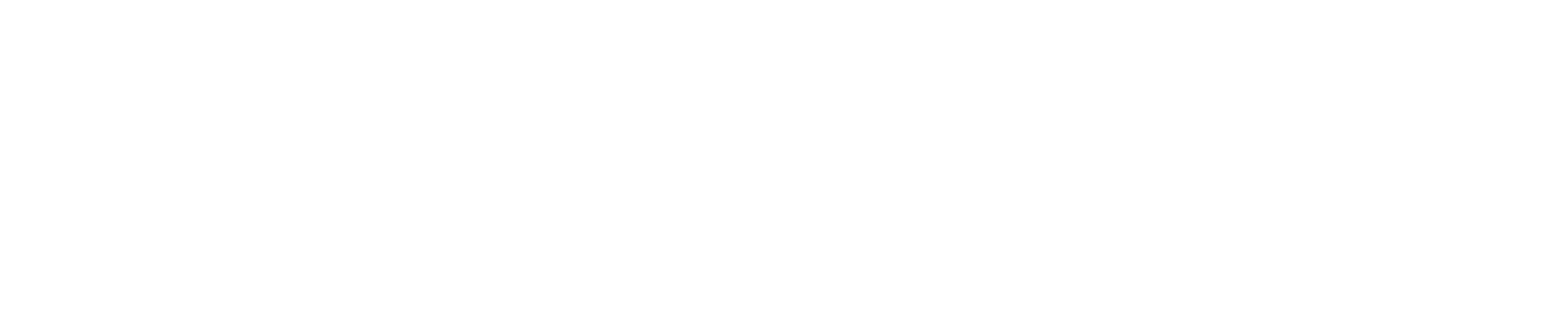

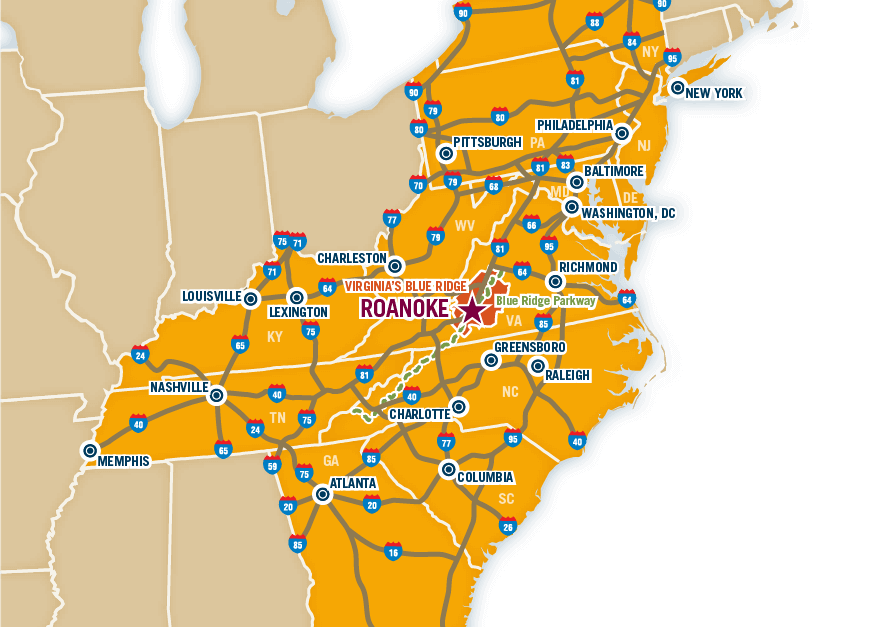

The Booker T. Washington National Monument is one of our most significant historical sites in Virginia’s Blue Ridge.

The monument is located near Smith Mountain Lake in Franklin County and is where Washington was born into slavery in April 1856. He would spend his first nine years living as an enslaved person before the Emancipation Proclamation would set him and his family free.

Washington would later go on to found the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama and emerge as an iconic leader and voice of the African American community in the United States, particularly for his work related to education and politics.

Here are 5 things we’re guessing you didn’t know about Booker T. Washington.

1. He was the first African-American on a U.S. Postage Stamp.

When the Post Office Department issued its stamp honoring Booker T. Washington on April 7, 1940, it was the first stamp in our nation’s history to honor an African American. The stamp was part of the Postal Service’s Famous Americans Series.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt received many petitions throughout the 1930s to feature Booker T. Washington on a stamp, and in 1938, acknowledged that Washington deserved consideration to be featured as part of the Famous Americans series.

Washington was again honored by the Postal Service in 1956 for the 100 year anniversary of his birth, with a stamp featuring an image meant to represent the cabin where he was born.

Learn more about the Booker T. Washington postage stamps >

2. He secretly funded efforts that helped advance the civil rights efforts in the United States, particularly the South.

Washington’s impact and legacy related to civil rights is complicated, to say the least. He faced criticism from other Black leaders, such as NAACP founder W.E.B. Du Bois, for telling Black Americans to concentrate on working hard and improving their own economic conditions through education and entrepreneurship instead of directly challenging segregation or fighting for political and social rights. Some viewed this as tolerance for Jim Crow Era segregation and a "separate but equal" philosophy.

Washington’s views were shaped, in part, by wanting to protect Black people from confrontation with whites and that cooperation would be the long-term solution to ending racism. However, despite his public comments that looked to avoid confrontation, Washington was secretly involved in financially supporting and contributing to many legal challenges against segregation and voter suppression. He also secretly invested in key Black newspapers and publications around the country to help bring attention to these issues and to help combat injustice and inequality.

Learn more about the debate between Washington & Du Bois >

3. He was an advisor to multiple U.S. Presidents.

With his work at the Tuskegee Institute and influence as a speaker and writer, Washington rose to national prominence, including among politicians. He was an advisor to U.S. Presidents William Howard Taft and Theodore Roosevelt, and he also hosted President William McKinley for a visit to Tuskegee.

Washington was also one of the first African Americans to be an official guest of a president for dinner at the White House, receiving an invitation from President Roosevelt.

According to this article by The History Channel, there was outrage among white southerners upon learning of the dinner invitation, with one Memphis newspaper describing it as “the most damnable outrage which has ever been perpetrated by any citizen of the United States.”

Learn more about Washington's dinner with Roosevelt >

4. He was part of a program that helped create 5,000 schools for Black children in rural communities across the South.

You see a passion and commitment to education throughout so much of Booker T. Washington’s legacy, but perhaps nowhere is it more evident than in his work and partnership with Sears CEO Julius Rosenwald to help create over 5,000 schools for Black children throughout rural communities in the South.

The Rosenwald Rural Schools Initiative was created to help combat the extreme inequity between what was spent on white schools compared to black schools in the South, despite the idea of things being “separate but equal.” The Rosenwald Fund would provide financial support, architectural blueprints, and guidance for Black communities on how they could build places for their children to attend school.

Washington also prioritized developing and training future teachers at places like Tuskegee, so they could return to their own communities to help educate the next generation.

It’s estimated that this initiative helped educate over 660,000 children, more than ¼ of Black children in the South.

Learn more about The Rosenwald Schools >

5. He was the superintendent of the Christiansburg Institute in Montgomery County.

While you might have known about Booker T. Washington’s connection to Franklin County, did you know he had a local connection to Montgomery County? From 1896 until his death in 1915, Washington served as a Superintendent at the Christiansburg Institute. The school was established in 1866 to educate freed slaves and help prepare them for freedom.

When Washington became involved in 1896, he changed the school’s curriculum from traditional subjects like reading, writing & history, to a more vocational-based approach, similar to the model he used at Tuskegee. The staff was entirely African American and it included many Tuskegee graduates. The Christiansburg Institute would go on to become one of the most highly-respected African American schools in the country.

Learn more about the Christiansburg Institute >

To learn more about Booker T. Washington and his remarkable life, we encourage you to plan a visit to the Booker T. Washington National Monument in Franklin County.

In addition to the exhibits that will educate you about Washington’s life, you can also walk the grounds on a relaxing 1.5-mile trail and check out the farm & garden areas to see what life was like on the farm during the 1850s.

Booker T. Washington National Monument - Location Information

Booker T. Washington National Monument

12130 Booker T. Washington Highway

Hardy, VA 24101

(540) 721-2094

Website >